Corporate Complicity in Atrocity

Corporate responsibility has shifted from voluntary Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) to binding legal, civil, and criminal liability for companies implicated in international crimes such as genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, or apartheid. Technologies, infrastructures, financial services, and digital platforms are instruments that can sustain systems of oppression rather than neutral tools. This legal and moral shift is captured by the UN report A/HRC/59/23, authored by Special Rapporteur Francesca Albanese, which characterizes the Israeli military and economic apparatus in the occupied Palestinian territories as a “genocidal economy”, invoking the legal definition of genocide under international law. Drawing on the Genocide Convention (1948) and relevant jurisprudence of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and international tribunals (see A/HRC/59/23, § 48–52), the report underscores that corporate involvement – whether through the provision of technology, weapons, or commercial services – can constitute complicity when such actions contribute to creating “conditions of life calculated to destroy” a protected group. Albanese stresses that, in this context, corporations cannot claim neutrality: they are considered part of what she calls a “joint criminal enterprise,” where the economic system itself – including corporate supply chains – sustains a genocidal apparatus.

The report also reiterates that corporate responsibility, as articulated in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, extends beyond risk mitigation to proactive disengagement when human rights violations rise to the level of international crimes. This approach aligns with recent case law, such as Okpabi v. Royal Dutch Shell Plc (2021), where the Court of Appeal in The Hague held Shell liable for failing to prevent abuses by subsidiaries in Nigeria. Similarly, the EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD), adopted in 2024, establishes binding obligations for companies to conduct human rights due diligence across global value chains, including the possibility of economic sanctions and civil liability. These developments confirm that the UNGPs, though non-binding, are increasingly treated as interpretive standards.

Companies may incur not only civil but also criminal liability under international law for contributing to or facilitating war crimes and genocide. The Special Rapporteur calls for sanctions, arms embargoes, and corporate reparations – potentially through mechanisms like an “apartheid wealth tax” – to redress the harm caused.

Businesses and Armed Conflicts: Corporate Complicity Between Moral Responsibility and International Criminal Law

International criminal law, as codified in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC), extends liability beyond state officials to corporate executives when their actions amount to aiding and abetting war crimes or genocide. A significant precedent is the Lafarge case (France/Syria), where the multinational cement company is accused of financing armed groups, including ISIS; in 2022, the French Court of Cassation confirmed the possibility of prosecuting the firm for complicity in crimes against humanity. This case highlights that ignorance is no defense: companies have a proactive duty of due diligence, especially in conflict zones.

The A/HRC/59/23 report details how leading technology and industrial corporations – including Google, Amazon, Microsoft, IBM, HP, Palantir, Leonardo, and Carrefour – form part of an ecosystem that, through contracts and strategic partnerships, delivers advanced digital infrastructures and critical technologies to the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). A prominent example is Project Nimbus, a $1.2 billion contract (2021) with Google and Amazon, providing cloud services, AI analytics, and facial recognition used for surveillance and targeting in Gaza (see §40–41). The report underscores that such technologies cannot be considered neutral. Microsoft, Google, and Alphabet’s AI systems have been described by an IDF colonel as “a weapon in every sense” (§41). Palantir has intensified its support since October 2023, providing predictive policing platforms and real-time battlefield data integration, thereby facilitating automated targeting decisions (§ 42).

Under the UNGPs and the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, companies must conduct human rights due diligence – identifying, preventing, and mitigating adverse impacts linked to their operations or business relationships. For tech companies, providing digital infrastructure for military operations in Gaza may constitute material complicity (Rome Statute, Art. 25).

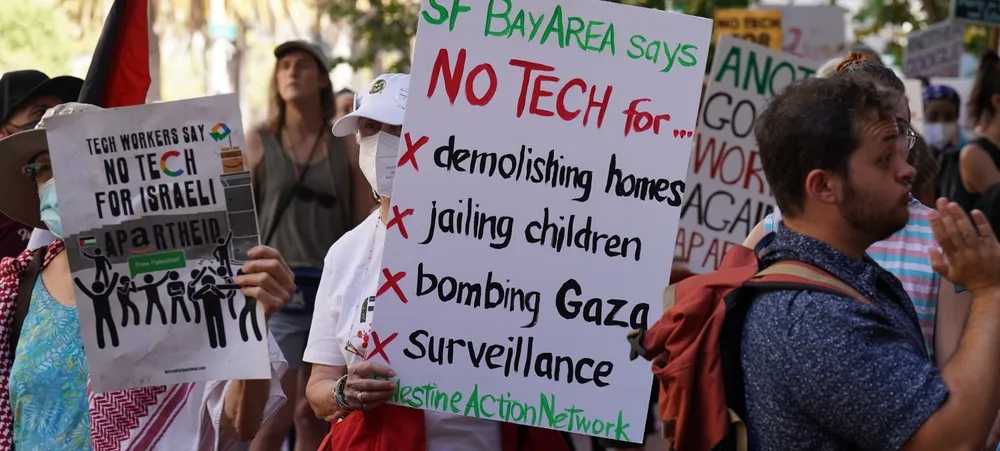

This analysis implicates not only governments and corporate leaders but a collective system of responsibility involving multiple actors – from organized civil society to universities, financial institutions, and individuals as consumers and professionals. Discussing this report ultimately raises the question of who can and must exert pressure to change the status quo. In this context, global civil society plays a decisive role, offering concrete models of mobilization and tools to demand transparency and accountability from corporations.

Two significant examples of this engagement are the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement and the Atrocity-Free Tech initiative.

BDS, founded in 2005 by over 170 Palestinian civil society organizations, is a global non-violent movement inspired by the struggle against South African apartheid. It calls for ending occupation and colonization, full equality for Palestinians, and the right of return. Its strategy revolves around promoting boycotts, divestment, and sanctions to exert economic and reputational pressure on governments and companies that profit from violations of international law in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. BDS cites companies like Chevron, Intel, Dell, HP, Carrefour, AXA, Google, and Amazon as complicit. According to the movement, these actors “fuel an economy of repression” by providing infrastructures that enable mass surveillance, movement control, and military operations, potentially linked to war crimes or crimes against humanity. BDS campaigns have compelled companies like Veolia and Orange to exit the Israeli market. Veolia sold all its Israeli contracts in 2015 after losing tens of billions of dollars in international tenders, while Orange ended its contract with Partner Communications in 2016 after six years of structured pressure. These examples show that civil mobilization can influence corporate decisions.

Atrocity-Free Tech, developed by the independent Norwegian platform Lysverket, is an initiative that promotes technology “free from atrocities,” meaning not involved in human rights violations or armed conflict contexts. It combines ethical divestment, reputational pressure, and promotion of alternatives complying with international standards. The project explicitly calls on companies to adhere to the UNGPs and the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, which impose a stringent obligation of human rights due diligence: companies must identify, prevent, and mitigate negative impacts of their activities and publicly account for the measures taken. In high-risk areas, this means heightened due diligence (UNGP Principle 7), with stronger preventive measures. In this sense, Atrocity-Free Tech is not merely a moral appeal but a normative advocacy initiative aimed at building accountability mechanisms for companies operating in sectors with a high risk of complicity in international crimes.

Both initiatives confirm civil society’s central role in enforcing transparency and “know and show” principle set by the UNGPs art. 17-21.

Instruments and Platforms for Corporate Accountability

If initiatives such as BDS and Atrocity-Free Tech represent bottom-up pressure tools, there are also academic and institutional platforms that provide legal evidence and practical tools to strengthen corporate accountability. The 2023 report Investor Obligations in Occupied Territories (University of Essex) is one such example. The document, authored by Chiara Macchi, Tara Van Ho, and Luis Felipe Yanes, examines the case of the Norwegian Government Pension Fund (SPU) and demonstrates how institutional investors can also be deemed complicit in international law violations if they finance companies operating in Israeli settlements in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. It argues that due diligence requires investors to divest or influence companies to avoid complicity.

Another important tool is the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre (BHRRC), an independent non-governmental organization with an international network that monitors and documents human rights violations by companies in over 40 countries. It maintains a database of 200+ legal cases and comparative analyses on corporate accountability.

Finally, the Justice Beyond Borders platform maps national laws in 216+ jurisdictions enabling prosecution of international crimes. Although focused on individuals, it is relevant for corporate actors where corporate criminal liability is recognized, reinforcing the idea that corporate responsibility extends under universal jurisdiction.

Why does this concern us all?

Traditional due diligence only verifies suppliers and business partners. But enhanced due diligence, as outlined by Principle 17 of the UNGPs, goes further: it requires companies to assess the impact of their activities on vulnerable populations, to analyse risks related to military or dual-use supplies, and to identify any connection with oppressive regimes or illegal settlements.

We live in a world where cloud services, social networks, and algorithms are not neutral tools. Every euro invested, every service used, can fuel a chain of violence or empowerment.

As consumers, professionals, and citizens, we have the power – and the responsibility – to choose atrocity-free platforms, support divestment campaigns, and demand rigorous HRDD criteria.

Indifference is a form of complicity. Corporate collusion means drones guided by servers, AI selecting targets, or goods produced on confiscated land.

As a professional and civil community, we can – and must – demand audits, engage in ethical investment, and support initiatives like BDS and Atrocity-Free Tech.

Silence is not neutral. If companies fail to change, we must change the market with our choices. Every choice, even digital, is a political act.

Leave a Reply